Hidden Pioneer

February 28, 2022

By:

Addie Parker

Addie Parker is a freelance journalist and is a junior golf instructor based in Midlothian, VA.

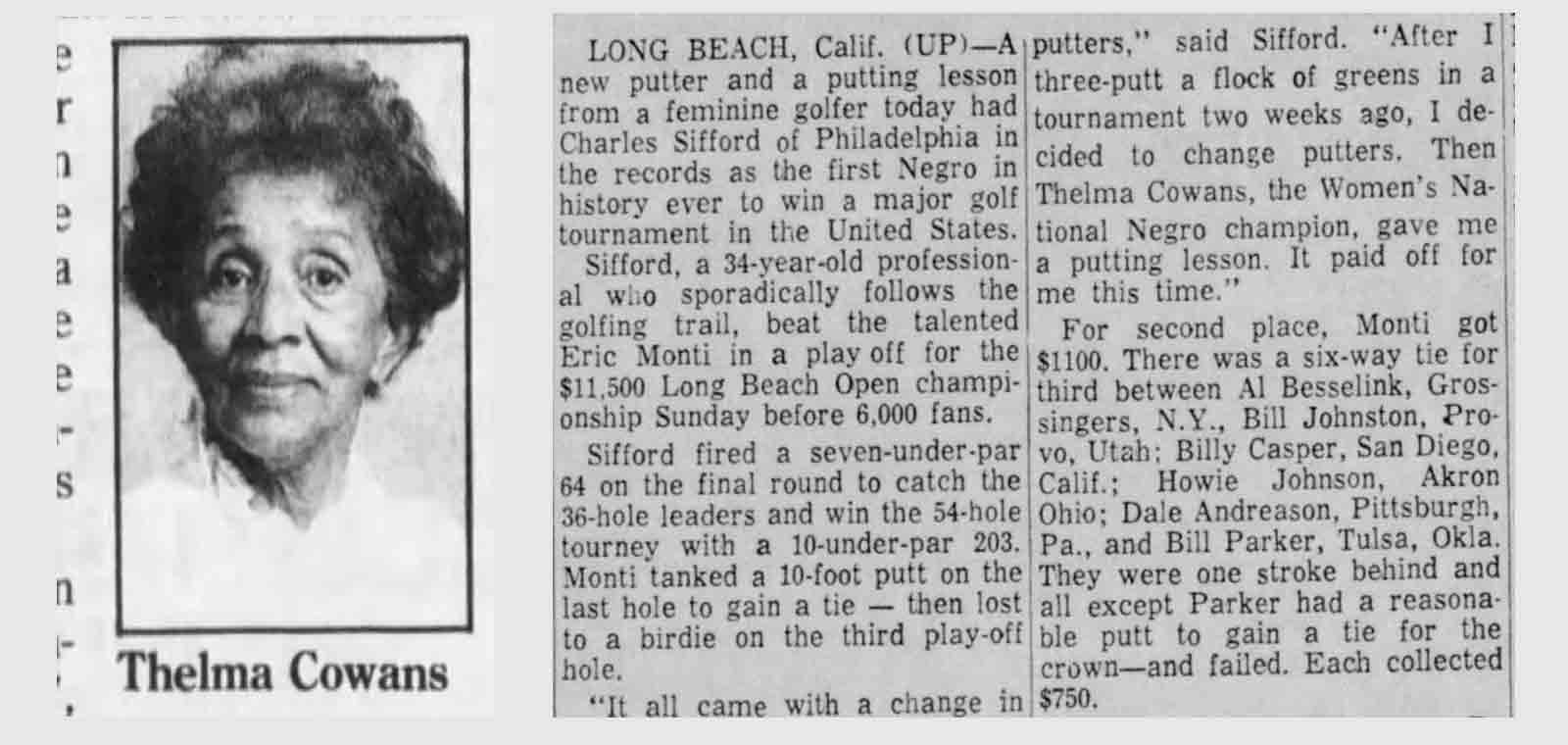

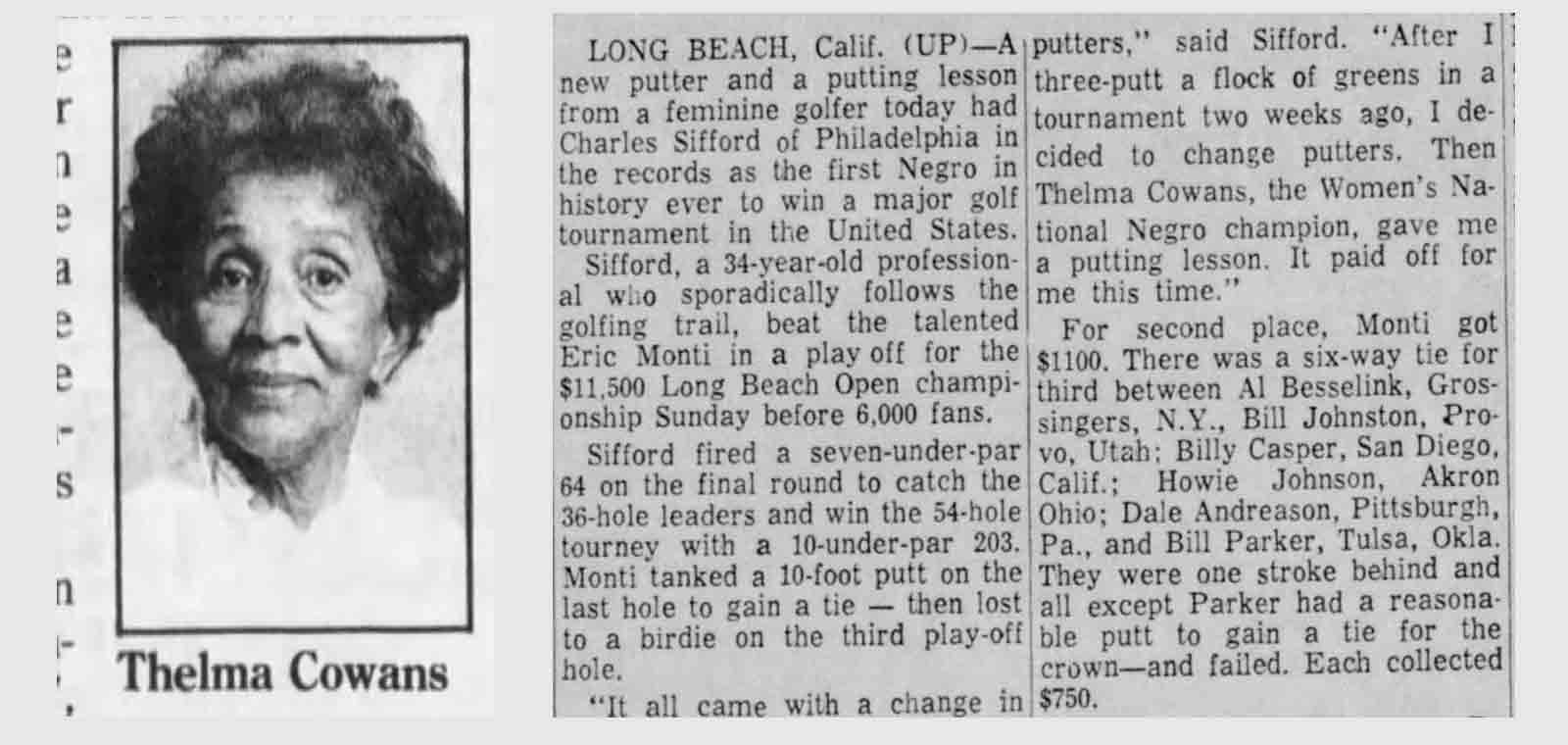

Thelma Cowans Blazed A Trail For Black Women Golfers

February 28, 2022

By:

Addie Parker is a freelance journalist and is a junior golf instructor based in Midlothian, VA.