The Extraordinary Adoption Journey of Jenny Lee-Smith

November 9, 2022

Steve Eubanks is a New York Times bestselling author and historian for the LPGA.

November 9 is International Adoption Day, and the month of November is Adoption Awareness Month in the United States. This is the first in a series of stories to celebrate the miracle of adoption.

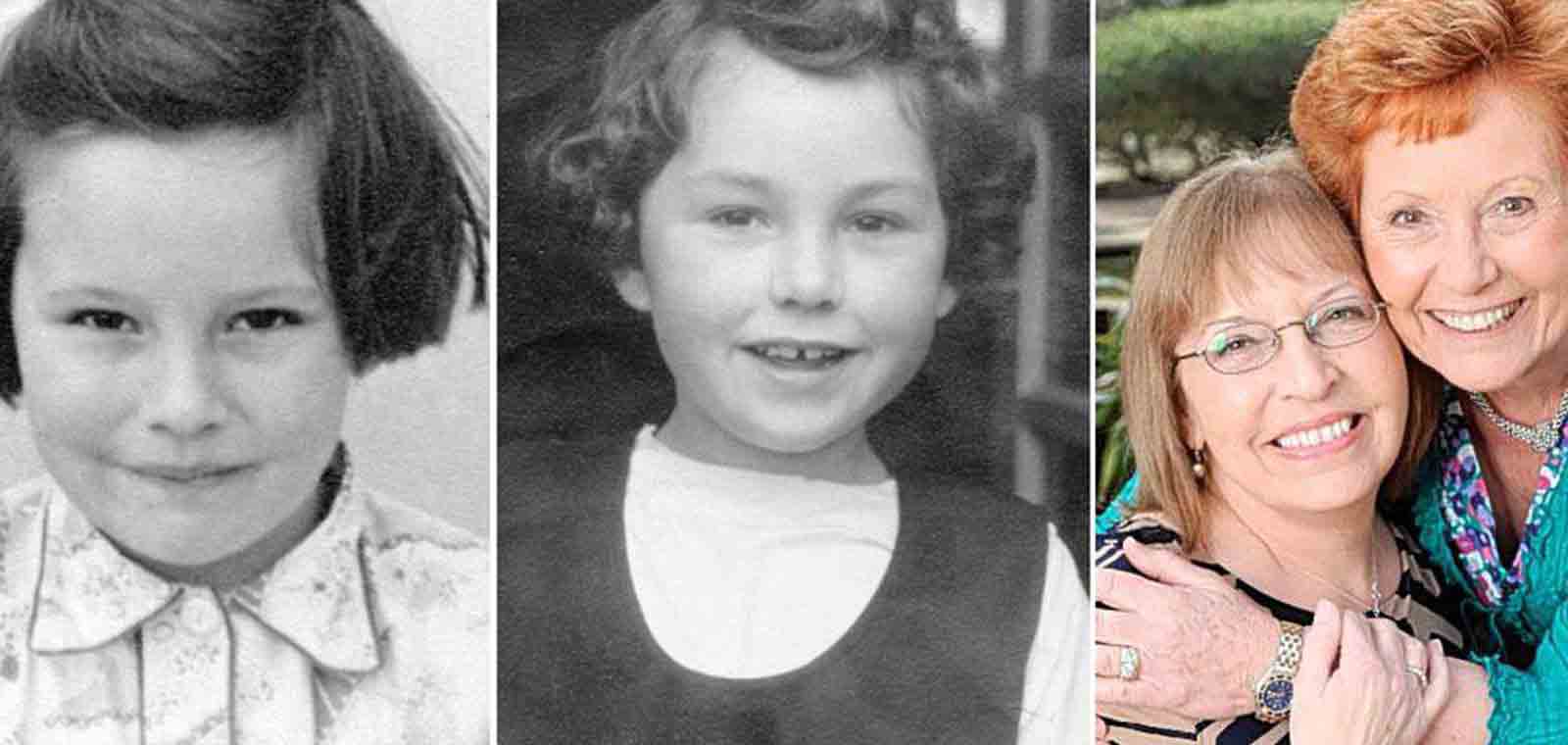

That is how Jenny learned she was adopted.

****

****

****